Privatisation, Privatisation or Privatisation?

Posted: September 18, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Privatisation, Privatisation or Privatisation?An article in the Hackney Gazette (4th September) saw the Labour council’s cabinet member for housing in Hackney, claim that tenants will have a choice on the option we prefer for matching the Decent Homes Standard. In response to this article, Hackney IWCA had the lead letter in this week’s Gazette. The Council’s obvious liking for ALMO (Arm’s Length Management Organisations) is something that we have observed for a while now and it is something we will continue to monitor. Islington IWCA are actively opposing ALMO in their borough and here we link to their website’s coverage of the campaign. Below we reprint the full version of our letter in response to Jamie Carswell’s comments.

Jamie Carswell (‘£450 million’ – Hackney Gazette – 4.9.03) tells us that we have three options available if we are to meet the Decent Homes standard in Hackney – stock transfer, Private Finance Initiative or ALMO. Because the council already knows how unpopular stock transfer and PFI are with most tenants, our cabinet member for housing paints ALMO in glowing terms but at the same time claims the choice between the three “genuinely isn’t decided”. Does anyone else smell a rat?

What we are being presented with is the “choice” between privatisation, privatisation and…privatisation. What choice is that? Can we trust a Labour government who have gone on record as stating that they wish to abolish council housing? And can we trust a Labour council whose record on “consultation” consists of listening to what the community says and then going ahead and doing what they themselves want anyway?

Hackney Labour Party tells us that with ALMO, rights of tenants and council employees will not be affected and it is simply a means of putting in extra money and increasing tenant participation. But if that was the motivation, the Chancellor Gordon Brown could sign the cheques tomorrow and draw-up new laws guaranteeing tenants a bigger say in how their homes are run without setting-up an ALMO.

Once again, Labour offers us a sham consultation in an attempt to sugar the privatisation pill.

Yours

Peter Sutton

Hackney IWCA

For more information on the IWCA’s policies on this issue see www.iwca.info

Housing benefit frustrations

Posted: July 30, 2003 Filed under: Hackney Council, Media Comments Off on Housing benefit frustrationsletter in Hackney Gazette (July 2003)

A few weeks ago you published some letters from Hackney Council apologists for the state of their Housing Benefit “service”. As a benefits advocate for a number of tenants & residents in Shoreditch I have this week had to write – for the third time – to Keltan House demanding very basic information about the progress of claims submitted in 2001. The frustration felt by myself and those who I am trying to assist is obvious.

I was involved with the campaign to rid Hackney of ITNet and I am pleased that they have been given the boot they deserved, but we should not tolerate the self-serving deception being foisted upon Hackney benefit claimants by councillors and senior officers. While they pretend that all is rosy, claimants all over Hackney know the deplorable truth, still being dragged through the courts for rent and Council Tax arrears that they have no control over.

My next port of call will be to the Local Government Ombudsman, where so many have gone before. As a Housing Benefit officer (boo, hiss!) for 15 years – in another London borough I hasten to add – councillors and managers should be ashamed at the hardship their residents are being put through. And to pretend that the service is working to an acceptable standard is just taking the proverbial pee.

Carl Taylor

Hackney Independent Working Class Association

Responses to Crowded Out

Posted: June 24, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs, Schools Comments Off on Responses to Crowded OutLast week we printed a copy of a Guardian Education article on closing schools in Hackney. Interestingly, in the same week we found out that Laburnum Primary in Haggerston had been taken off special measures but was still to be closed. Below are responses to the article from the head of the Learning Trust and a governor of Stormont House School. Tomlinson spins a nice angle on the story but it’s revealing that a man who argues he wants to” raise the level of public debate” on education in Hackney should so blatantly disregard the concerns of parents, teachers, pupils and support staff at Laburnum and Kingsland by closing down both schools.

Closing Kingsland

I was concerned at a number of aspects of your article (Crowded out, June 17) concerning the closure of Kingsland school in Hackney by the Learning Trust.

I was astonished that nowhere did you state clearly the reason the Learning Trust took action to close Kingsland. In November 1999, Ofsted inspected the school and found it failed to provide a satisfactory standard of education. That has remained the situation throughout the last three and a half years. Consequently pupil numbers plummeted as parents and children declined places at the school. The Learning Trust is not prepared to have parents send their children to such a school.

It is relatively easy to suggest that the school should have been kept open another year until Mossbourne Academy opened. It is harder to identify a reasonable message we could have sent to parents whose children were to start at the school in its last year. “Please send your children to this failing school that we intend to close” is hardly a responsible position for the Learning Trust or any local education authority to have taken.

As you rightly note, for existing key stage 4 pupils we indicated we would make an arrangement with local further education colleges. This is exactly what we have done, as you again record. To call this chaos is an odd use of words. I recognise that leading articles linking chaos and Hackney have been common in the past. This, however, is no longer the case.

The Learning Trust has conducted all the business of closing Kingsland school in the proper public arenas. The proposal was quite legitimately challenged, and as a consequence was passed to the schools adjudicator. This independent public body supported the trust’s proposal to close Kingsland and the arrangements for the continuing education of those pupils still in the school.

We want to raise the level of public debate around education in Hackney and in this spirit we welcome criticism, even when for the sake of emphasis it parts company with reality.

Mike Tomlinson

Chair, the Learning Trust, Hackney

Will sense prevail?

As a school governor in Hackney for 17 years, I found your article did not tell the whole story surrounding the closure of Kingsland school.

In autumn 2001, governors of Stormont House school, a highly successful special school in Hackney, were asked by the then LEA to second our headteacher, Angela Murphy, to Kingsland school with the clear objective of turning round what was then a failing school.

However, less than halfway through her time there, the LEA (even before the Learning Trust took over) started consulting on the closure of Kingsland. It is a testament to the leadership shown by Angela Murphy that, notwithstanding closure proposals hanging over the school, Kingsland has now come off special measures within weeks of its closure.

Therefore Kingsland school is only dying because the Learning Trust was determined to kill it.

What is clear is that the lack of democratic accountability of the Learning Trust has allowed the situation to develop, with the council’s education scrutiny panel apparently powerless to intervene.

Must we wait until the Ofsted inspection this September for sense to prevail?

Andrew Bridgwater

Hackney

Crowded out

Posted: June 17, 2003 Filed under: Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs, Schools Comments Off on Crowded outReprinted here is a long article from the Guardian’s Education supplement. It covers the recent closure of Kingsland School but also looks at the bigger picture of why Hackney Council is closing schools and the creep towards privatisation being imposed by national government policy with its specialist schools drive and local government with its unwillingness to listen to the concerns of working class residents. Looking at the article, you might ask yourself why a school in Stoke Newington which is obviously successful and serving a generally more middle class catchment area can get £1 million in extra funding whereas a school like Kingsland which is improving from its “failing” status can be axed. Class sizes or class discrimination?

There is chaos in the London borough of Hackney as one school is forced to close and another is forced to take extra pupils. Melanie McFadyean reports

17th June 2003

The Guardian

Almost half of all Hackney’s children go out of the borough to school. Many of them have no choice. Of the borough’s nine secondary schools, one is for boys, three for girls, three are denominational and two are coeducational. One of the co-eds, Kingsland, is about to be closed. The other is Stoke Newington school, which, under its current headteacher Mark Emmerson, is much sought after and over-subscribed.

In April, Emmerson sent out a letter to parents. (I declare an interest here: I am a Stoke Newington parent.) As a result of the closure of Kingsland, itself a matter of pain and controversy for its pupils, parents and teachers, Emmerson was told by the Learning Trust, Hackney’s education authority, that his school would be taking an extra 29 pupils in year 7 in September. (Had the Learning Trust tried to put 30 in they may not have got it past the relevant committees, as 30 constitutes an extra class.)

Given the overcrowding, why was the school expected to take on so many extra pupils? Because, said a Learning Trust spokesman, it was deemed to have the space.

Emmerson didn’t agree. “We will be too overcrowded,” he wrote to parents. “With increased numbers, the first things to break down are the systems we have for managing students; behaviour and attendance are particularly hard to maintain. We do not have enough staff. We do not have enough money, we do not have enough room. It is suggested that we convert offices, dining rooms and the staff room into classroom space.”

In order to maximise space, Emmerson told parents he would need £1,170,000. “We’re having to fight for every penny because there isn’t contingency in the budgets to deal with these issues,” he told the Guardian. “Success is a hard-won prize and very easily damaged, and that’s why I am fighting for the resources. We are dealing with the fall-out from the Kingsland closure and there is no recognition that this has an impact on schools around them.”

By dint of relentless pressure on the Learning Trust and the DfES, Emmerson has secured a substantial tranche of the £1m-plus. A compromise has been struck. But meanwhile what is happening to the Kingsland pupils and their teachers?

“We are not helping Kingsland,” Emmerson explained. “The 29 students will not be from Kingsland families.” So where are the Kingsland children going?

Of those on roll at the beginning of the year, some have already been “shuffled out”, as the Learning Trust’s director of pupil services, PJ Wilkinson, explains. There is a lot of turnover, or “churn” as it is known, in Hackney, so as places became available during the year, kids were moved on. Some Kingsland teachers weren’t happy about the way this was done: according to one teacher there, pupils would simply not turn up and it would transpire they had been moved. Wilkinson says the speed of changeover was surely “a good thing, not a bad thing”.

At the end of May, Wilkinson told the Guardian: “We are seeking school places for approximately 150 students in Kingsland years 7 and 8 in alternative local schools. So far these places have mainly been identified in out-of-borough schools, although there have been small numbers placed at several Hackney secondary schools.”

But 105 in current years 7 and 8 have not yet been placed for September. “I cannot say where they are going. Many have turned down offers, some are holding out for Stoke Newington,” says Wilkinson. “We believe they will be placed but they will be subject to considerable pressure when places come up.

“If they have turned down two places, we’d have to take the position that parents are being unreasonable. They have to take responsibility. We want consent not coercion, but coercion comes at the point at the end of the process. We are trying to steer them without using the maximum harshness that we are allowed to use. It’s terribly difficult.”

There have been problems, too, for current year 9 students. At the beginning of May, a Learning Trust representative told the Guardian that the remaining 141 pupils would go to the Sarah Centre, a new “14+” centre at Hackney Community College, for the two years of their GCSEs, where they will apparently have a pupil-teacher ratio of one to eight. But it would appear this key stratagem was not, in fact, signed up. Jackie Hurst, head of marketing at the college, said: “We are in the middle of considering it.”

On May 20, PJ Wilkinson said the college had given agreement to go ahead, although contracts were still being written. But on May 22, Hurst said: “There is no definite news on the movement of children from Kings land school; we won’t know anything [until] some time after June 2.”

On June 3, a spokeswoman at the college told the Guardian: “Our governors are hoping to take a final decision on whether Kingsland pupils will come to the Sarah Centre on June 10. Nothing has been agreed.” In the event, the deal was rubber-stamped.

Asked what she thought of the trust’s assumption that the centre would sign up, Hurst said she supposed it “was a risk they [the Learning Trust] took. Presumably they had no other option.” The Learning Trust said: “This agreement with the colleges was included in our submissions to the adjudicator on the closure of Kingsland. This has been agreed at progressive levels of detail over the last few months.

“We have a strong partnership with the colleges, who have been happy to speak to students over the last few months on the understanding that they would deliver, as is now the case.”

The impression that the Sarah Centre was definitely signed up was underlined by the Learning Trust’s directions to pupils at Kingsland for choosing their GCSEs.

The pupils going to the new centre were shown their GCSE options at a meeting in school on April 9. A few weeks later, another option sheet was given out. It was a list of seven compulsory subjects, with students asked to select three choices from a grid of subjects. There was no language option, Turkish and French having been deleted from the former list. A note explained that foreign languages will be on offer “where appropriate”. GCSE students will have been relieved to hear last week that there would now be “opportunities to study foreign languages”.

But the choices are tight. A student could not, for example, study geography, history and sociology – only one would be on offer. In the compulsory vocational list, from which students must pick one, are business studies, construction crafts, food technology, health and social care, leisure and tourism and motor vehicle engineering. There may be students to whom none of these appeals. Others might like to do more than one.

“This is a dumbed-down curriculum, and for some of our kids this year 9 to 11 period is the one chance they have – and it’s a chance that’s in danger of being blown,” says one Kingsland teacher.

The teachers were told of the proposal to close the school in July last year, and were offered a special one-off payment as an incentive to stay for the final year, a proposal that was to be clarified at the start of the academic year. The NUT didn’t get copies of the proposals until the end of February. It had asked for an across-the-board payment, but the plan was instead to pay between £3,000 and £6,000, with higher rates going to senior management.

There were strings attached. Anyone suffering more than 10 days sickness during the year would be paid only at the discretion of the Learning Trust. “Failure to accept the above in its entirety,” wrote Wilkinson, “will result in withdrawal of the scheme.”

People felt “deleted”, as one Kingsland teacher put it, and some decided to get out early. “Some of these are people who would have been prepared to work for another year or two to see the kids through. There will be continuity problems for kids going on with their year groups without the teachers they know.”

Redundancy would be an option, although redeployment was not ruled out. In May, Cheryl Newsome, executive director of people management at the Learning Trust, sent letters giving an estimated redundancy/early retirement quotation. But she added that final decisions would be made by the director of education and would be “based on the contingency of the service. If there is a suitable alternative post… the organisation will not authorise redundancy.”

Mark Lushington, spokesman for Hackney Teachers Association, which represents NUT members, says: “Many people have made plans on the basis of being made redundant and do not want to be redeployed.” They may have little choice.

Mark Emmerson says he would like to have seen Kingsland left open for another year until a planned new school, Mossborough Academy, opens in September 2004.

“Kingsland is an improving school, it isn’t going down the pan and if they’d waited, all the issues would have been sorted [and] it might have provided a better educational environment for the students.” Anne Shapiro, head of nearby Haggerston school for girls, agrees. “A lot of us feel the school is making progress. The school could have been given more time to improve and been allowed to see if it was possible to come out of special measures.” (The school is due for an inspection at which this is expected to happen.)

Wilkinson counters that Kingsland was a dying school and it would have been a “betrayal” of Hackney parents to keep it open. “If you move students en bloc you reproduce the same problems. You can’t shake off reputations; it’s better to break the thing up than keep it together.

“Fresh Start didn’t work. The new schools weren’t new enough and the bad reputations were transferred.”

There is a subtext at work in this story. Hackney desperately needs new schools, which it will get only if it conforms to the government’s strategy of setting up city academies. When Emmerson went to the DfES with Wilkinson in May, he recalls, “we suggested some recording of the pitfalls experienced during this school closure. The argument was that if there are to be more city academies, schools will be closed and there’s a cost involved for other schools. They want three city academies in Hackney and one they want is planned for the Kingsland site.”

The new city academies, of which Mossborough is one, are politically sensitive. Wilkinson insists they are not part of a drive towards privatising public services. “I’m very careful about the word privatisation. It’s not what an academy is – it’s state, no fees, no profits, not like private schools.” But pressed on the fundamental difference between city academies and ordinary secondary schools, he said there was “an interest in encouraging enterprise to bring money into schools”.

There will be more school closures to clear the way for city academies. If the chaos surrounding the Kingsland closure is anything to go by, one can only hope the DfES learns from the bumpy ride in Hackney and stops to question the ethos and financial arrangements that are the subtext of these upheavals.

The Learning Trust

Hackney education authority was in serious trouble when it was disbanded in August 2002. It had previously been partly privatised after consultants KPMG told the education secretary that outsourcing was the answer. Nord Anglia took over some key areas of the borough’s education functions. But in October 2000, an Ofsted inspection criticised the council for failure to provide “a secure context for the improvement of educational standards”.

In August 2001, the government announced plans to hand over Hackney’s education provision to an independent, not-for-profit trust. The secretary of state appointed three members to the trust’s board, including the chair and two “independent experts”; a director of education and three members of the senior management team would also be included. Other members would be selected from local heads and governors.

The trust was to be contracted to run education for the borough to “secure maximal revenue and capital funding for Hackney’s schools, including the exploration of a PFI/PPP bid to bring the condition of Hackney’s schools up to standards appropriate to the 21st century”.

Mike Tomlinson, the former chief inspector of schools, became the first chairman of the Learning Trust when he retired from Ofsted in April 2002.

A spokesman says its contract is “managed by the council and they retain ultimate authority for education in the borough. They must approve our annual plan [which] includes our bud get. Councillors sit on our board, and… the education scrutiny panel can review us against any of the terms of the contract. In the memorandum of understanding [annex to the contract] we undertake to respect the role of democratically elected representatives and the council’s scrutiny committees in reviewing decisions and the strategy of the trust.”

Only one member of the board is an elected representative of the local population; the others are selected and therefore largely unaccountable to users. It is this aspect that worries critics of this new semi-privatised LEA, who feel it is undemocratic. Local NUT divisional secretary Mick Regan says: “There is a serious lack of democracy in the Learning Trust, which is in effect a quango.”

Sink or swim in the Basin

Posted: June 15, 2003 Filed under: Gentrification / Regeneration, Media, Olympics Comments Off on Sink or swim in the BasinBelow we reprint an article from The Guardian about regeneration in London. It’s particularly interesting in the light of London’s proposed bid for the Olympics and the push by Labour to get Hackney people supporting it. This article asks the question, do local people benefit from regeneration schemes.

A multi-million pound development is creating 30,000 jobs in a run down area. But, reports Colin Cottell, local people are missing out on the much-needed work

A flagship project with the promise of jobs for the long term unemployed. What could be better for a deprived area of London that sits next to pockets of incredible wealth, but never seems to benefit from the ripple effect?

Occupying a site the size of 60 football pitches three miles west of Oxford Street, Paddington Waterside is a gleaming collection of offices, upmarket homes and holes in the ground that will turn into yet more gleaming offices and upmarket homes. Out goes the seedy prostitution and bedsits image that has dogged the area and in comes shiny 21st century living.

Like east Manchester after the Commonwealth Games, Paddington Waterside is supposed to turn an employment desert into a thriving part of town, creating an extra 30,000 jobs.

Mobile phone company Orange is building its new European headquarters building, the Point, next to one of the canals that run through Paddington. Marks & Spencer is also moving its HQ to the area. Just 11 acres of the site, bought for £85m by a developer, will see £600m spent on it before completion.

Yet on a sunny afternoon last week, two young men kicking a football about on a local council estate, less than half a mile away from the main Paddington site, say they have missed out.

Although in its brief history the regeneration of the area has already spawned several thousand jobs, neither men say that they or residents on the estate have gained anything.

“I don’t know anyone who has found work at Paddington Basin,” says Mark Bradshaw, aged 22. Mr Bradshaw has been in and out of work for the past four years.

“Lots of my mates on the estate are out of work,” he says. What about the construction companies who say they are crying out for people? “They are lying,” he says.

Who to believe? Those who say that urban regeneration projects such as Paddington Waterside bring jobs and prosperity to nearby communities or those who complain that it always the locals who lose out?

One thing is certain, however. More than a decade after Canary Wharf put urban regeneration on the political and social agenda, the question of who gains from massive projects such as Paddington Waterside, and a host of others, including London’s Olympics bid, shows no signs of going away.

Sue Hinds, head of community employment at the London Borough of Tower Hamlets, home to Canary Wharf, says the answer to people who ask if local people are winners is “yes and no”. She adds: “It depends who you talk to. Some employers will think that local people won’t have the skills they need. Some local people will think the jobs are not for them.”

However, in Tower Hamlets as elsewhere the hard facts tell their own story. Employment, including 5,000 construction jobs, may have risen to 60,000 at Canary Wharf, but in its shadow there are around 9,000 residents out of work.

Granted, unemployment has come down, but at around 12% it is still more than twice that of London as a whole, says Ms Hinds, and excludes the large number of people of working age who are economically inactive – including 57% of women.

According to Robert John, an adviser to Canary Wharf, around 7.5% of those employed at Canary Wharf live in Tower Hamlets, up from 4.5% in 1997. But compare the actual number of non-construction jobs held by Tower Hamlets’ residents – around 3,000 in 2001 – with the 150,000 jobs in the borough, and it is clear that there is still along way to go.

The situation has improved as local people’s aspirations have risen, says Mr John. However, more still needs to be done. “We need to work on ways of making places like this not hostile to local people,” he says. “It is not that are there are no jobs, or a lack of opportunities, but poverty of attainment. People have low aspirations. They don’t think they will get those jobs,” says Colin Middleton, program manager at the City Fringe Partnership, which works in deprived areas such as Hackney. However, everyone involved in regeneration agrees that limited aspirations are only part of the problem.

There is a mismatch between the skills employers require and those possessed by local communities, says Mr Middleton. “The skills needed are NVQ Level 4 and above. The majority will have NVQ Level 2 or below.”

Mike Noakes, general manager for BAA Rail, which operates the Heathrow Express at Paddington station, admits: “We do have to look further afield sometimes. High customer service type skills are required for frontline positions such as drivers and staff who work on the trains, and sometimes these are the ones local people don’t have.

“Some of these jobs have been filled by locals, but not so many up to date,” he says. Jobs such as baggage handlers have been easier to fill locally, he adds.

For other employers the only criterion is ability to do the job. “We don’t see it as whether someone is an insider or an outsider, but will they make a decent lawyer or not? The postcode is absolutely irrelevant. We wouldn’t employ someone just because they lived on the Isle of Dogs,” said Iain Rodger, Head of PR at legal firm, Allen &Overy, who employ 200 staff at Canary Wharf.

Nigel Hugill, chairman of Paddington Waterside Partnership, the private sector lead consortium redeveloping Paddington, says that as unemployment has fallen the task of getting the remaining jobless into work has become more difficult.

Kay Buxton, the Partnership’s chief executive, says they have made progress in helping local people to compete.

Since 1999, Paddington First, their non-fee jobs agency has helped find work for over 2,500 people. “Some 40%-50% of people getting jobs through Paddington First live within two miles of Paddington Waterside, and 60% live within [the public transport] zones one or two,” she says.

Employers involved in the Paddington development are doing their bit. All the main contractors and sub-contractors have agreed to advertise their vacancies with Paddington First.

It was generally easy to recruit local people, says Trevor George, construction manager for Wates Construction, who following a customised training course took on three of the 12 trainees employed. Mr George says that the experience left him “pleasantly surprised.”

However, according to John Hodson, director of programmes at Renaisi, a not-for-profit organisation specialising in regeneration, the beneficial effects of large scale construction projects on local employment are often limited. “The contracts are tendered out to major companies and a small proportion will go to local residents,” he says. And even where companies set up training programs, the numbers involved will be “a small proportion of the total workforce”, maybe 20% on a major construction site.

Higher up, the situation is even worse, says Caroline Masundire, managing director of regeneration recruitment consultants Chase Moulande. Despite a severe shortage of planners and surveyors, she has never known a local person get one of these jobs. “It’s men in suits – people who move in for two years and then bugger off.” At least that’s what communities think, she adds.

Even where locals do find work it may be short-lived, says Ms Hinds. “The anecdotal evidence is that people are not staying in their jobs. Most of the unemployed have been out of work for between four months and a year. People get jobs, then go back to being unemployed.” Other anecdotal evidence shows that when local people get well-paid decent work they move out of the area to “somewhere a bit greener,” she suggests.

Figures from Canary Wharf back this up. “Between 1997 and 2001, 640 people moved out of Tower Hamlets after starting work at Canary Wharf,” says Mr John. Those people who move in, by contrast, tend to be “at the top of the deprivation ladder,” says Mr Middleton. “So it starts again – a vicious circle.”

Professor Andrew Church, from the geography department at the University of Sussex, adds: “The community changes as the development occurs.” And because new groups moving into an area may not have the skills necessary to take up the available jobs local unemployment remains high.

Ms Hinds accepts that consistently shifting populations are a reality of inner city life and that this makes it difficult to reduce unemployment for good.

Nevertheless, she remains optimistic. “I think it is changing slowly. But it is changing,” she says.

Whether such change ultimately leads to local people getting their fair share of jobs remains to be seen.

Red Pepper on Hackney's Financial Turmoil

Posted: November 4, 2002 Filed under: Hackney Council, Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs Comments Off on Red Pepper on Hackney's Financial Turmoil

by Andy Robertson – from this month’s Red Pepper magazine

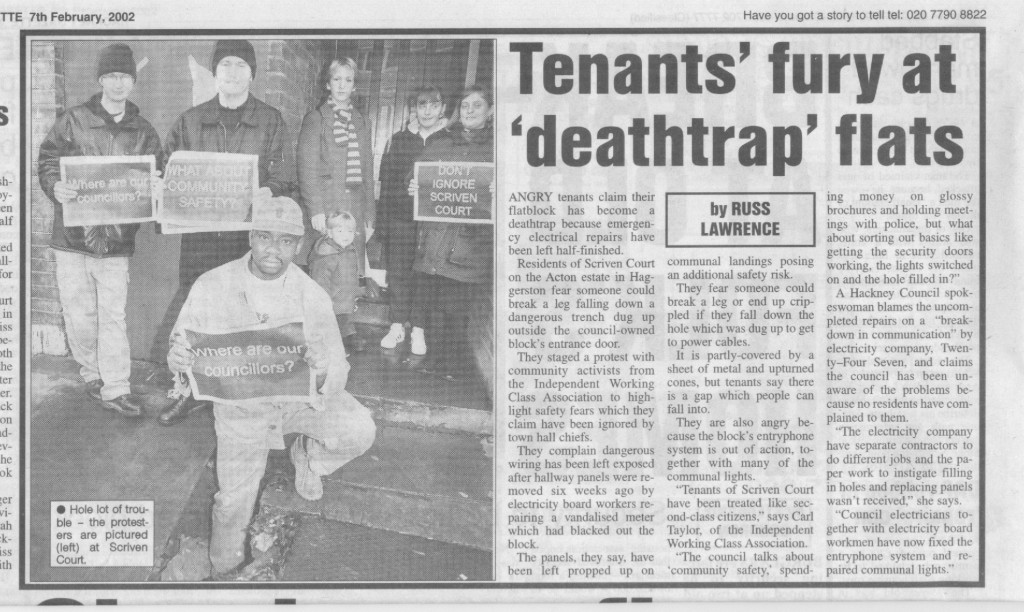

Tenants' fury at 'deathtrap' flats

Posted: February 7, 2002 Filed under: Community Safety, Media Comments Off on Tenants' fury at 'deathtrap' flats

Junk the jargon

Posted: December 19, 2001 Filed under: Gentrification / Regeneration, Media Comments Off on Junk the jargonLetter in Guardian Society 19th December 2001

It’s good to see that to encourage black and ethnic minority (BME) involvement in regeneration in Lambeth, the jargon is to be junked in favour of plain English (Ethnic barrier, December 12). Now how about the rest of us?

As a member of an organisation concerned about the impact of regeneration/gentrification on working class people of all races in Hackney, I would like to make it known to housing minister Lord Falconer that it’s not just BMEs who are disadvantaged by not understanding the often euphemistic nonsense spouted by New Labour clones in their rush to socially cleanse deprived areas of their working class majorities.

Plain English would be of assistance to us all. Better still, a bullsh*t detector.

Carl Taylor

Hackney Independent Working Class Association

Letter in Hackney Gazette 27th September

Posted: September 27, 2001 Filed under: Hackney Council, Media Comments Off on Letter in Hackney Gazette 27th SeptemberYour political coverage over the last few weeks has been excellent. We have read about the butchery of funding to groups that support Hackney’s most vulnerable, while councillors give themselves and their corporate friends more of our money – often in secret meetings. We have discovered – as if we didn’t know already – that you need to earn on average £57,000 pa to buy a home in London’s poorest borough, and that the majority of households earn far less than £30,000. Meanwhile, as youth services are decimated, youth crime escalates. And privatised workers – the more the better according to our McLabour bigwigs – see their working conditions and living standards plummet.

Put it all together and you can see what kind of Hackney our “leaders” are creating for us. Of course, they will say, our sacrifices are necessary to save Hackney from itself. But who is it being saved for? Certainly not the majority, when all we can expect is more deprivation and exploitation. To return “the usual suspects” – Labour, Tory, LibDem or Green – would be like those proverbial turkeys voting for Christmas.

Carl Taylor, Suffolk Estate.

Taking the Shine off Pinnacle's Glossy Picture

Posted: July 6, 2001 Filed under: Gentrification / Regeneration, Hackney Council, Media, Privatisation / Sell Offs, Tenants & Residents Associations Comments Off on Taking the Shine off Pinnacle's Glossy PictureRoger Tayor of JSS Pinnacle paints a glossy picture of how the company could secure more work for its profit-driven ventures (Inside Housing June 15). The reality of its existing operations in the Shoreditch Neighbourhood in Hackney is more prosaic. Despite being in the area for over two years, it has failed to significantly improve the performance of Shoreditch neighbourhood (judging by the published key performance indicators) in relation to the rest of the housing management service.

Readers need no reminding that Hackney Council provides the most expensive service which is substantially below par, so JSS Pinnacle does not realy have to try very hard to do better.

In addition, it allegedly managed to overspend its repairs budget by around £600,000. The council, without consulting other residents, decided to generously allow JSS Pinnacle to pay back that deby over two years. This year, again without specifically consulting residents (the item was hidden in a turgid committee report), the council agreed to wipe the slate clean, as it would take too long to pay back and damage Shoreditch tenants’ interests.

This is an interesting point. When JSS Pinnacle make profits, the company gets to keep its ‘return’ on capital, they are not spread round the borough. When it allegedly overspends, the council spreads the losses over the HRA [the name of the budget for day-to day spending oncouncil housing]. Is it possible to know what JSS Pinnacle really makes on its Hackney operation? My advice to others is don’t touch them with a bargepole.

John Calderon. Chair, Dalston Neighbourhood Panel.

Tenant leader and the Chair of the former Hackney Tenants Federation (FOHTRA) takes the fight into the house journal of the housing professionals, Inside Housing, 6 July

Recent Comments